Towards a New Architecture

Le Corbusier

Towards a New Architecture (Vers une architecture), published in 1923, is one of the most influential manifestos in 20th-century architectural theory. It presents Le Corbusier’s call for a fundamental rethinking of architectural design that reflects the technological and social transformations of the modern age.

This essay argues the RELEVANCE of Le Corbusier’s definition of architecture in Towards a New Architecture

This essay was written as part of a supervised architectural history submission for the University of Cambridge architecture programme and is presented here to demonstrate academic research and writing.

Do you think Le Corbusier’s definition of architecture in Towards a New Architecture is correct and is it still relevant today?

Le Corbusier’s definition of architecture in Towards a New Architecture has had a profoundly significant influence on the architectural landscape we see today. His work stands out as pioneering the popularity of the modernist movement. In Towards a New Architecture, Le Corbusier envisioned a revolution, meticulously detailing the applications of his vision and exploring the connections to fundamental principles and engineering frameworks as a method of designing architecture. Le Corbusier’s concept of ‘Mass Production Houses’ was not merely a technical model for architecture but intended as a profound philosophical shift in how architecture could serve society.

However, as modernist architectural ideas evolved, the global influences of his work frequently failed to capture the nuanced essence of his original vision. Instead, many of these developments have become symbols of architectural and social failure.

This essay will examine how the reductionist interpretations of Le Corbusier’s ideas neglected to consider a humanistic and holistic approach to architectural design, contributing to the construction of mass dystopias unrecognisable from the utopian ideals Le Corbusier desired to manufacture.

While his ideas on design were far ahead of their time, many of the values they were framed on focused too greatly on the technical rather than the human; it reflects how the world requires an architectural philosophy that embraces architectural legacies and traditions with a central focus on the importance of thoughtful consideration of the complexities and desires of human experience in architectural design.

Le Corbusier offers us an architectural solution, ‘Mass Production Houses,’ a motion that he describes as ‘ based on analysis and experiment,’ framing this as not merely a technical response but as a philosophical shift, repeating the word ‘spirit’ about the production, conserving, and living of these ‘Mass Production Houses’.

Yet the modern consensus on the mass production of architecture suggests that this concept has ultimately failed. Le Corbusier’s initial concepts of this idea possessed architectural merit, as they harmonised an amalgamation of his design principles. However, it seems more apparent that those who have used his work as inspiration have transcribed these ideas, consistently excluding fundamental elements which structured the liveability of a design. This has left us with carbon copies, soulless buildings, and a distortion of Corbusier’s ideal.

Le Corbusier’s idea of the ‘Radiant City’ may have had some influences on modernist approaches; he proposed a thoughtful challenge to his audience, emphasising how ‘We must make a choice between the static city and the dynamic city.’ Yet the influences of his work, particularly those of mass production, are nothing but static.

Cité Radieuse in Marseille, France, is an example of how Le Corbusier’s designs have become largely associated with failure, as his distinctive typologies are deeply associated with undesirable housing and crime. When Le Corbusier designed the structure, it was an example of how housing could be combined with communal spaces.

Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, Missouri, exemplifies how Le Corbusier’s designs have been inelegantly replicated across the Western world. Designed by Minoru Yamasaki in the modernist style, it demonstrates the neglectful simplification of Le Corbusier’s ideal, disregarding many of the crucial ideas that allowed his initial developments to succeed, such as the importance of well-designed, functional housing that would foster a vibrant and thriving community.

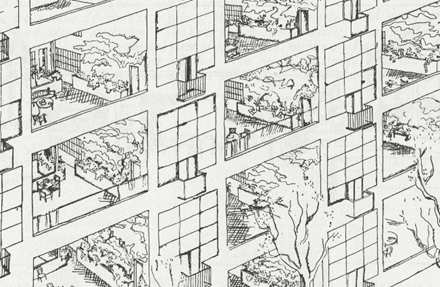

Its appearance is far removed from that of The Hanging Gardens ‘Freehold Maisonettes,’ which focused on embracing architecture’s co-habitation with nature, as the planned playgrounds, ground-floor restaurants, and landscaping of the development were all deemed to be too expensive by the federal housing administration.

Pruitt-Igoe and the countless reiterations resembling it speak to the immense failures that have occurred in the last century. Modernism has failed us; it has been taken advantage of as an acceptable standard, allowing developers to construct sterile concrete deserts that fail to foster the vibrant communities that Le Corbusier envisioned, and instead, contribute to urban blight and social disintegration. Ultimately leaving the less fortunate in society with no other option than to reside in a circuit board ‘machine’ cities.

Le Corbusier’s description of the desires of the ‘modern man wanting only a monk’s cell to look at the stars’ [1] appears to misinterpret the desires of post-war society, acting as more of a poetic statement to support his design principles than a thoughtful consideration of the likely cultural change that would occur in a post-war society. Le Corbusier’s perception of the austerity and simplicity in modern man’s desire for architecture seems to be a miscalculation of societal responses to national traumas, this oversight is evidenced by the later population of trends like the American Dream that created a counter-revolution to Le Corbusier’s vision, resulting in an expansive embrace of all that embodies status and luxury, a trend that, although consistently changing, maintained an encompassing nature of consumerism throughout the latter half of the century.

While Le Corbusier’s principles may have had potential for successful influence, the historical placement of Le Corbusier’s writing in an interwar period just years after the First World War and the shadow of the impending Second likely had a significant negative impact on the later success of the influence of this work that resulted in distortions like Pruitt-Igoe. The aftermath of the wars left large numbers of people in need of affordable housing, resulting in immense pressure to find a solution and as the upper and middle classes constructed sprawling suburbia and single-home developments, many of Le Corbusier’s developments like Cité Radieuse lost popularity, reframing themselves as more architectural monuments than nuanced architectural solutions and reduced the influences of his vision as a tool for post-war recovery rather than a visionary movement. ‘The pursuit of simplicity and minimalism in modernist urban planning, while initially seen as a remedy to wartime destruction, often resulted in impoverished, uniform spaces that denied the diversity and texture of earlier urban forms’ This dissolution of variety directly impacted these communities, only further isolating them. The result was verticalized reiterations of the previous centuries’ slum-like urban environments they sought to replace.

However, despite concerns about Le Corbusier’s values for architecture, the resulting influence of this work does not accurately reflect his vision, instead, it is a product of an unforeseen shift in culture. The developments inspired by his work, are an entity of their own, without the necessary components for successful implementation.

Le Corbusier’s vision lacks a human approach, as engineering principles largely inspire his writing. His description of architecture in the form of mechanical industrial principles may have appealed to the interests of people at that time; the world had not yet changed, but he was an influence on its revolution. Initially, his comparison of architecture to aeroplanes and automobiles seemed misplaced; how could these mechanical technologies be appropriately used to explain something as broadly embedded into our lived experience as architecture? I reflect that it was this very approach that helped to popularise his vision. Conceptualising architecture as tangible and technical, allowing understanding and engagement with the people of the time.

However, by focusing so deeply on functionality, he loses sight of architecture’s real purpose, to foster human life, spaces have a profound ability to impact our lives, memories, and sense of home. Corbusier describes a house as ‘a machine for living in’, but excessive focus on processes and functionality removes character. When Le Corbusier visualised these concepts, his work was nuanced, a rebellion against architectural rigidity. Yet since then, his concepts can be seen in the architecture that dominates our landscape. His vision is no longer revolutionary; it is no longer modern. The culture has shifted, and humanity desires a new revolution: the re-embracement of ornament and of personality.

This is what Le Corbusier’s vision fundamentally lacks. It is too reductionist. It is a protest to the culture of the time, but the nature of protests is that they are often short-lived. Design preferences in our ever-changing world will inevitably eventually go out of style and later be re-embraced as cultural and political views shift and morph – this is what our architecture should do too. It should be flexible and malleable to change and grow with us.

Le Corbusier’s vision for a modern architectural revolution was a radical rejection of all that came before him. His statement, ‘We must start again from zero,’ calls for a complete reset of our architectural environment through the replacement of all existing architecture in favour of his mechanically influenced, efficiency-driven vision for our architectural environment, a true revolution. Yet the impracticality of this vision seemed nothing less than impractical and extravagantly fanciful. ‘Le Corbusier’s desire to rebuild the world from zero failed to account for the deep-seated architectural traditions and cultural patterns that had evolved over time.’

More importantly, it is an antagonist of historical preservation through architectural expression. The beauty of our built world is not just through the artistic value of our constructions but also through architecture’s ability to tell our cultural stories.

We should not ‘(destroy the old world)’ but embody it, embracing the traditions formulated and refined over thousands of years; ‘preserving architectural legacies and traditions can create a dialogue between past and present, shaping the way cities and communities evolve.’ [1] The design iterations that have stood the test of time have done so for a reason, they are loved and admired by the people who experience them, multi-generationally and cross-culturally. That is our architectural legacy, an architectural reflection that resembles the variation that possesses the nature of humanity.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boyer, M. C. (1992). The City of Collective Memory: Its Historical Imagery and Architectural Entertainments. MIT Press.

Colomina, B. (1994). The Politics of Architecture and the History of Modernism. Princeton Architectural Press.

Corbusier, L. (1923). Towards a New Architecture. Architectural Press.

Corbusier, L. (1933). The radiant city: Elements of a doctrine of urbanism to be used as the basis of our machine-age civilization. Faber and Faber.

Dreier, P. (2019). The impact of modernist urban projects: Pruitt-Igoe and beyond. Urban Studies Journal, 56(5), 823-839.

Features., C. F. (Director). (2011). The Pruitt-Igoe Myth [Motion Picture].

Alyssa Denise Walsh

University of Cambridge

2024