Journal

NOTICE

This website is in the midst of its transition, marking a new chapter beyond the alyssawalsh.com site that has carried my work for seven years. You may find portions still taking shape.

Nuclear Semiotics

Containment as Culture

Architectural Strategies for Communicating Nuclear Waste Across Deep Time

Section ONE

Introduction

Nuclear technologies have become central to the modern world. They provide reliable energy production, support important medical treatments and contribute to scientific advancement. These benefits come at a cost that unfolds across deep time. High level radioactive waste remains hazardous for periods that extend far beyond the duration of any established human civilisation. No recorded language, political structure or cultural tradition has yet endured for the time span in which such waste will continue to pose a threat to life. The challenge of preventing exposure is therefore not only a matter of engineering and geology. It is also a challenge of communication and culture.

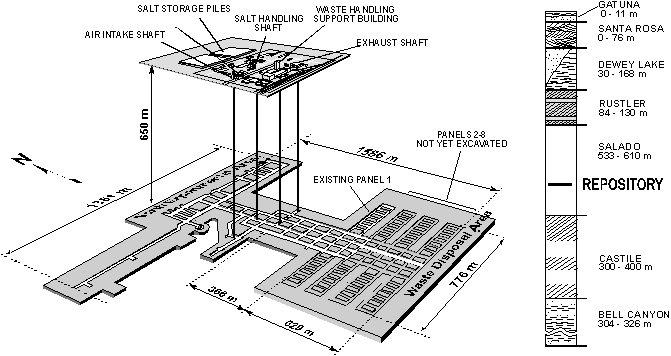

The field of nuclear semiotics attempts to address this problem. It asks how warnings might survive for thousands of years and remain comprehensible to people who may have no knowledge of our languages or technologies. The Human Interference Task Force first formalised this investigation in the early nineteen eighties, recognising that nuclear waste requires an enduring system of deterrence (Human Interference Task Force 1984). Sandia National Laboratories later proposed a multi layered approach for the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, ranging from immediate visual warnings to detailed scientific explanations intended for future decipherment (Sandia National Laboratories 1993). These studies acknowledge that any warning must communicate across vast cultural distances.

However serious obstacles remain. Written language is vulnerable to transformation. Symbols lose their meaning. Even the attempt to conceal a dangerous site poses risk. A sealed chamber without visible explanation might tempt excavation rather than prevent it. Proposals that rely upon the stability of social institutions, such as the idea of maintaining a perpetual order responsible for preserving the warning, require a form of historical continuity that cannot be guaranteed (Sebeok 1984). Approaches that focus solely upon hostile architecture risk becoming a curiosity for future societies. What appears threatening to one culture may appear sacred or intriguing to another.

The consequences of failure are severe. If a future community misinterprets or disregards a warning, the result would be direct exposure to radiation. Communication must therefore operate at multiple depths of understanding. Neuroscientific research shows that some visual signals are processed instinctively within the human brain, particularly within the amygdala, which responds rapidly to potential danger without conscious interpretation (Öhman 2005). These findings indicate that architecture can communicate threat even if language or cultural context is lost (Larson et al 2009).

This essay engages with that complexity. It proposes an architectural response that remains comprehensible through both instinct and interpretation. It examines existing warning proposals, analyses the communicative success of prehistoric art and monumental inscription, and incorporates psychological research on fear perception. The purpose is to develop a design that does not merely endure but continues to speak, reminding future societies of a threat that must remain contained.

Section Two

The Communication Problem and the Architectural Responsibility of Deep Time

Modern nuclear waste repositories are designed primarily as feats of engineering. They are constructed deep within stable geological strata so that hazardous materials remain physically isolated from ecosystems and human activity. The Onkalo repository in Finland exemplifies this approach, with engineered barriers and bedrock conditions chosen to ensure containment over extraordinarily long periods of time (Posiva 2012). Although physical security is necessary, even the most robust geological repository remains vulnerable to human interference. A future society, unaware of the danger, could disturb the site through excavation or resource extraction. The issue cannot be addressed by engineering alone. It must also be understood as a profound communicative responsibility.

Architecture must therefore confront a time scale entirely unfamiliar to human experience. Traditional monuments mark a specific moment or commemorate a finite period. They presume a cultural context that understands their meaning. The design of a monument for nuclear waste must reverse this assumption. It must communicate with people who may know nothing of the world that created it. It must remain intelligible in a future that bears no resemblance to the present.

The concept of nuclear semiotics emerged in the late twentieth century in response to this challenge (Human Interference Task Force 1984). It recognises that meaning does not naturally persist. Written language mutates. Symbols shift in interpretation. The most durable architecture can be reimagined by later cultures in ways that oppose the intentions of its creators. A defensive structure becomes a sacred temple. A tomb becomes a treasure vault. A warning becomes a mystery.

One proposed strategy has been to reduce reliance upon communication entirely. If nuclear waste facilities can be fully concealed and forgotten, perhaps the safest approach is to allow collective memory to dissolve. The Onkalo project demonstrates this idea. Once fully sealed, its surface is intended to blend gradually back into the landscape. Future people may be unaware that anything lies beneath (Posiva 2012). This effort to eliminate temptation relies upon the hope that the site will not be rediscovered. However history suggests that humans are drawn to hidden or unexplained structures. Curiosity is a powerful force. Forgotten places have often become the subject of exploration.

Another strategy is the deliberate creation of hostile environments that prompt instinctive avoidance. The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in the United States has been the focus of extensive research into such ideas. Proposed configurations include jagged landforms, irregularly tilted monoliths and geomorphic arrangements that appear wrong to the human eye (Sandia National Laboratories 1993). The purpose of these designs is to inspire fear or disinterest at a pre conscious level. Yet, in time, such landscapes could also be read as sacred or symbolic. They might invite investigation rather than prevent it.

Social strategies have also been proposed. Thomas Sebeok suggested that knowledge of nuclear danger be preserved through a living tradition. A permanent group or order could maintain warnings as part of ritual life, embedding the hazard into cultural memory through narrative and taboo (Sebeok 1984). The strength of this approach lies in its engagement with collective identity. However it demands unbroken continuity of cultural systems. Civilisations rise and fall. Institutions are vulnerable to transformation, repression or collapse. Memory can be rewritten or lost.

A more comprehensive response was developed through the work of the WIPP semiotic programme, which advocated multiple layers of communication intended to operate simultaneously (WIPP Expert Group 1993). Immediate visual signals would provide a basic warning. Pictorial narrative would explain the presence of danger. Written and technical records would offer detailed information to any highly literate future audience. This approach accepts that meaning must be redundant. If one layer fails, others may remain legible.

Architecture is capable of enacting such redundancy. Built form is simultaneously a spatial experience, a symbolic presence and a potential archive for information. It can address people through emotion while also enabling interpretation. It operates through the human body and the human imagination. For nuclear warning to remain effective across vast periods of time, architecture must employ that full communicative potential.

In order to succeed, a nuclear warning monument must express more than simple prohibition. It must reveal that the hazard continues far beyond the moment it was buried. It must demonstrate that its purpose remains vital. It must declare that generations have understood the threat and taken steps to protect those who might come later. A static structure risks becoming archaic and detached from the present. A living structure that evolves through time can avoid that fate. Continuity of meaning requires continuity of form.

This responsibility is architectural as much as political or scientific. Once radioactive waste is sealed beneath the earth, the only active voice that remains is the built environment that surrounds it. Communication becomes stone, route, scale and shadow. Architecture is the final advocate for the safety of future life. Its language must remain clear when all others may fall silent.

Section THREE

Existing Proposals and Their Limitations

As nuclear semiotics developed in the late twentieth century, several approaches emerged that sought to communicate danger across deep time. These approaches differ significantly in method and intention. Each offers valuable insight, although none provides a complete solution. Understanding their capabilities and limitations is essential in order to form a more reliable architectural response.

The first significant category consists of hostile physical markers designed to provoke instinctive avoidance. Research at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant considered the transformation of the landscape into a threatening environment that would repel intruders. The proposals examined strange and uncomfortable spatial geometries, with fields of sharp monoliths, irregular surfaces and unsettling forms that signal harm through emotional force rather than technical clarity (Sandia National Laboratories 1993). Such architecture seeks to communicate through pre linguistic recognition. It attempts to cause retreat before curiosity or interpretation can take place. Although compelling, this approach is vulnerable to reinterpretation. A future society might see this environment as sacred or mysterious, and this change in perception could invite exploration rather than discourage it. What one age fears, another may revere.

A second approach focuses on written or symbolic information. One research strand investigated the placement of information panels in multiple languages around nuclear sites, arranged in concentric patterns intended to record linguistic evolution. The expectation was that future translations would be added over centuries, each further from the centre than the last, so that the monument itself would reveal the passage of time. This concept acknowledges the fragility of linguistic continuity and offers a form of adaptation through periodic renewal. However the written word remains susceptible to the disappearance of literacy. Entire writing systems can become opaque within a few hundred years. Without a stable tradition of translation, the warning could become a silent script whose meaning is lost.

The third approach is rooted in cultural or ritual preservation. Thomas Sebeok proposed that warnings might be sustained through myth and tradition, with a dedicated group responsible for retaining and transmitting the message (Sebeok 1984). This method aims to embed the warning not in a passive marker but in the living structure of human belief. Ritual offers resilience if social systems remain stable. Yet it relies upon continuity of institutions that history rarely supports over long periods. Most religious and political orders eventually collapse or transform in ways that may erase or reinterpret inherited messages. Collective memory can prove fragile when confronted with upheaval.

A fourth approach is concealment. This approach holds that avoidance can be ensured through absence. If the waste is completely hidden and forgotten, there can be no risk of interference. The example of Onkalo in Finland demonstrates this philosophy, where the surface will eventually be restored to resemble unmarked landscape after sealing the repository (Posiva 2012). The difficulty is that forgetting itself cannot be controlled. Future populations encountering unexplained subterranean structures may be driven by discovery rather than caution. Concealment invites excavation if it becomes visible again.

A more comprehensive strategy emerged in the proposals from the WIPP Expert Group, which suggested that warnings must be layered within multiple complementary modes of communication (WIPP Expert Group 1993). Visual deterrence, narrative signifying the presence of a lasting hazard and written scientific explanation were to be used together so that if one form of message failed the others might endure. This model acknowledges that a warning capable of surviving millennia must address both instinct and intellect. However this approach was not developed into a single cohesive architectural form that could organise and sustain renewal over time.

When examined together, these methods each respond to a specific dimension of the deep time challenge. Hostile environments speak to fear. Written language preserves records when literacy continues. Ritual embeds meaning in society. Concealment offers temporary protection if memory remains absent. None of these strategies addresses all of the requirements simultaneously. Communication must remain clear even if belief systems collapse, if languages shift, if symbols transform and if curiosity overcomes caution. The question remains how an architectural system might combine these strengths while reducing their vulnerabilities.

A nuclear repository will remain dangerous regardless of historical circumstances. It therefore requires a communicative system that is designed to evolve rather than degrade. The architecture must be capable of renewal. It must explicitly record the persistent nature of the threat. It must communicate in a language understood not only by the reflective mind but also by the instinctive body. Most importantly, it must express that the danger is not an artefact of the past but an ongoing condition requiring active memory.

This recognition prepares the ground for the design proposal developed in the following section. The deficiencies of existing approaches do not imply failure but rather indicate that the solution must be more ambitious. Architecture must protect the future by ensuring that the warning remains alive. It must foster a tradition of remembrance that continues through the physical environment itself. Only then can the message endure until the danger is finally gone.ts the warning not as a one-off message but as an evolving, living monument that grows with time, memory and responsibility.

Section FOUR

Memory Carved in Rock: Lessons from Prehistoric Art, Monumental Inscription and Deep Time

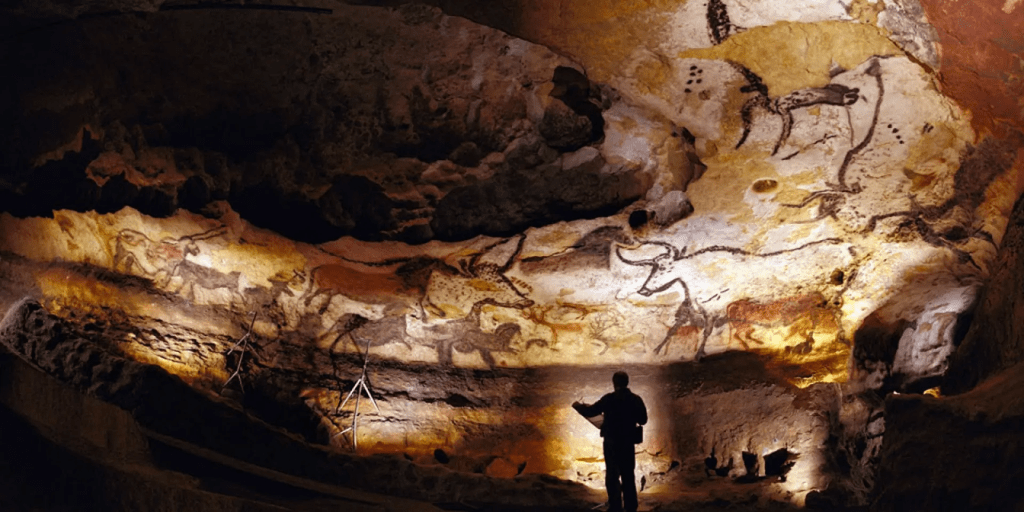

Humanity has always sought to speak to the future. Long before written language emerged, individuals worked pigment into stone so that their messages might outlive them. The deep caves of prehistoric Europe hold evidence of this desire. In the silence of Lascaux in France, where paintings are approximately twenty thousand years old, the walls depict a vivid population of animals crafted using iron oxide, manganese compounds and charcoal that continue to maintain their colour and form (Royal Society of Chemistry 2020). These pigments were chosen instinctively yet they possess remarkable geological durability. The surrounding environment has preserved them through stable temperature and low exposure to destructive elements (Britannica 2025). The figures of bulls and horses not only show representation, they reveal a clear intention that the image should remain visible far beyond the life of the maker.

Even older examples can be found within Chauvet Cave in the Ardèche region of France, where large felines and rhinoceros are drawn with precise shading capable of suggesting motion and depth. This art may exceed thirty thousand years in age and demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of illusion and visual narrative (Smarthistory 2023). Altamira in Spain likewise contains polychrome paintings of bison that have retained powerful visual impact despite the passage of time and the disappearance of the culture that created them (Smarthistory 2023). These sites demonstrate that representation on stone, when protected from the open environment, can survive much longer than written cultural history. The communication remains legible even as knowledge of the original society has entirely vanished.

A later expression of long term visual communication can be found in the monumental inscriptions of ancient Egypt. Hieroglyphs were cut into resilient stone so that the memory of rulers, beliefs and cosmology would remain intact long after their deaths. Many inscriptions have retained clarity more than three millennia after their creation (British Museum 2022). Although the writing became unreadable after the fall of the civilisation, the eventual rediscovery of meaning through the Rosetta Stone illustrates that the physical endurance of the inscription created the possibility for meaning to be recovered. The combination of durable material and deliberate symbolic form allows cultural transmission to survive through periods of total silence and forgetting.

These prehistoric and historic examples provide important guidance for architecture confronted by deep time obligations. They show that images and inscriptions carved into durable surfaces can preserve intelligible meaning without relying upon the continuity of language or the stability of institutions. They reveal that pictorial storytelling can create immediate recognition across cultural distance, because the human mind engages quickly with narrative scene making and depictions of living beings.

Contemporary research in neuroscience deepens this understanding. Studies show that fear responses are processed in the amygdala which responds rapidly to visual cues of potential threat without the need for conscious interpretation (Öhman 2005). Sharp angled shapes, disorienting spatial sequences and environments that imply instability or harm trigger discomfort and vigilance because they resemble conditions associated with danger in the evolutionary past (Larson et al 2009). These reactions appear consistent across cultures. The body interprets threat as a primary form of communication. Architecture can therefore address future viewers at the level of instinct, long before any symbolic or technical information is understood.

Together, these traditions of prehistoric art, monumental inscription and visual neuroscience indicate that a long term warning system must operate through durable materials, clear storytelling and innate emotional responses. A communication that seeks to reach people thousands of years in the future cannot rely upon language alone. It must be accessible through the shared human capacities for recognition, fear and visual memory. Stone reliefs can retain depth and shadow when text becomes silent. Images can speak when alphabets are lost. Physical form can evoke caution even when belief systems and technologies have changed in ways we cannot imagine.

The record left by past cultures proves that messages can survive beyond political collapse, climate change and cultural reinvention. For the guardianship of nuclear waste this is not simply inspiring evidence. It is a necessary precedent. The architecture that protects radioactive material must acknowledge that time is both its greatest threat and its intended audience. What remains must continue to communicate, even when all other forms of human expression have changed.

Section FIVE

Concentric Rings of Warning as a Living Monument

The previous sections demonstrate that no single semiotic or architectural strategy can ensure the long term communication of nuclear danger. A successful approach must integrate instinctive deterrence with sustained cultural transmission. It must also show that the threat continues rather than fades with time. The proposal developed here offers an architectural response that can evolve, that encourages remembrance and that embodies responsibility across many centuries.

The foundation of this proposal is the understanding that containment is a continuing act rather than a completed task. The monument proposed here is therefore not static. It anticipates the future and calls upon those who come later to participate in the work of warning. It seeks to reveal through its expanding form that each generation has inherited a duty to safeguard life from the buried hazard beneath.

5.1 Spatial and Temporal Organisation

At the heart of the site lies the deep geological repository, sealed and protected by engineered and geological barriers. Rather than marking the boundary of that danger with a fixed structure, the design introduces a wide region of separation between the hazardous core and the architecture that warns of it. The first outer ring is situated far beyond the technical safety radius. In doing so, distance becomes a visible statement about caution. The landscape around the centre remains unapproachable not only because of radiation risk but also because of spatial meaning.

The rings form a system of concentric enclosures. The current knowledge of nuclear danger is expressed in the innermost built ring. One hundred years later, another ring is constructed outside the first. The earlier structure remains untouched. This process continues at regular intervals indefinitely. The monument therefore becomes a physical archive of human understanding as time advances. The distance from the centre does not represent safety. Instead it reveals the persistence of the threat. The growing chapel of stone that encircles the buried waste becomes a chronicle of vigilance.

5.2 The Interior Zone as Communicative Deterrent

The region between the central chamber and the first ring communicates warning through spatial experience rather than interpretation. Neuroscientific research has shown that certain environmental cues can provoke fear or unease long before conscious reasoning intervenes (Larson et al 2009). Architecture can therefore operate on the instinctive body by shaping light, texture, scale and movement in ways that evoke caution. The interior zone of the monument applies this understanding.

The ground becomes uneven. Surfaces are fractured and disquieting. Paths narrow and corner abruptly. Light enters irregularly through angled cuts in the walls. The air may vibrate with discomforting stillness. The mind is not given stable geometries upon which to rest. There is no suggestion of welcome. Curiosity is challenged by unease. In this region, architecture acts as instinctive deterrent. Even without an understanding of radiation, a visitor can feel that the earth here is not safe. The intention is not to punish but to prevent. The environment itself encourages withdrawal.

5.3 The Rings as Narrative Archive

Beyond the interior zone, the rings become places of narrative communication. Each ring contains a sequence of carved reliefs that describe the origins and consequences of nuclear technology. The story is told through figurative imagery rather than linguistic inscription. It begins with the mining of uranium from the earth and then shows its transformation into energy and power. The panels record both positive and negative uses of radiation, including medicine and electricity but also environmental disasters. They depict the invisible movement of radiation from contaminated matter into living bodies and ecosystems. Finally, they show a decision to contain the danger and to mark its place for those who will come later.

This narrative gives voice to responsibility. It acknowledges the scientific achievement while arguing that the consequence is not temporary. It is a story that honours ingenuity while recognising the necessity of protection. Because it is a story in images, it does not require a shared language to be understood. A future society that recognises human figures in distress or landscapes harmed by energy will understand danger as a moral concern rather than a mythical curiosity.

The narrative never resolves into closure. Each ring repeats the same story, interpreted in the artistic style of the age in which it is built. Earlier interpretations remain intact inside later ones, forming a layered historical record. As the monument expands, it inscribes the repeating reminder that the threat has not ended.

5.4 Material and Structural Permanence

The selection of material must ensure that the monument remains legible for periods extending beyond the lifespan of any known architectural tradition. Stone with high density and weather resistance is essential. Granite or similarly durable rock can withstand erosion for as long as the waste remains dangerous. Reliefs are carved deeply enough to maintain visibility even as the surface slowly wears. In areas where greater protection is required, panels may be recessed within shallow niches that limit exposure to rain or wind.

The construction of each ring reinforces the foundation of the previous one. Structural integrity is not decorative. It is communicative, since collapse would signify neglect rather than warning. The monument is intentionally heavy and persistent. Its form declares that the buried material is not to be disturbed even within the most distant futures.

5.5 Renewal as Social Ritual

The renewal of the monument is ritual rather than maintenance. Each new ring is constructed not only to transmit information but to reaffirm the cultural responsibility to understand and respect the danger. The act of building becomes a form of remembrance. This task invites involvement from future communities and fosters a continuous intergenerational legacy of caution.

A system of planning would be required to ensure that resources and knowledge remain available for each renewal. Yet this does not imply a permanent institutional structure dependent upon political stability. The act of renewal becomes the structure. Knowledge persists because each generation must learn the meaning of the monument in order to contribute to its expansion. The monument teaches responsibility by requiring participation. Forgetting becomes difficult when the future itself is bound to the obligation of construction.

5.6 Spatial Journey and Perceptual Transition

The experience of approaching the monument reinforces understanding without reliance upon textual instruction. From a distance, the rings form a geometric horizon that signals the presence of human intervention. As the viewer nears, the mass and scale of the walls become imposing. Surfaces present depictions of environmental harm and bodily risk. The entrance into the inner zone is narrow and dark. The intuitive response is to turn back.

If one continues from the outer rings toward the heart of the site, the sensory experience becomes increasingly hostile. The monument thereby creates a consistent narrative movement from comprehension to instinct. Interpretation and emotion work together to discourage intrusion. The visitor understands, both intellectually and somatically, that continuing inward is a violation.

5.7 Architectural Expression of Deep Time

The most significant communicative gesture of the monument lies within its growth. The rings expand outward century after century. The physical distance between the outer ring and the central chamber becomes a visible measurement of time. This expansion demonstrates that the danger does not diminish. Every new ring proves that generations continue to regard the hazard as active and urgent.

Within the monument, the environment therefore expresses a message that language alone could never fully convey. It teaches that protection is unending. The architecture shows that containment is not a historical event but a living responsibility. This visual logic allows any visitor from any culture to understand that the site contains something dangerous that must remain sealed.

The growth of the rings also ensures that the message never becomes archaic. A monument fixed in a single era of design may lose legibility as cultural values shift. A monument that renews itself through time remains present to those who encounter it. It remains a contemporary voice for future generations.

5.8 Summary of Deep Time Responsibility

This proposal unites the lessons learned from hostile environments, monumental inscription and cultural ritual. It uses instinctive fear and narrative clarity as parallel forms of communication. It relies upon the durability of stone and upon a social structure of renewal that does not depend on political continuity. It ensures that the warning remains alive by making the architecture itself a living record.

A nuclear warning does not succeed through silence. It succeeds through remembrance. The architecture proposed here transforms the notion of containment into an enduring cultural act. It recognises that the future will have its own challenges and uncertainties. It presents a message that is not bound to any present belief or system of knowledge. Instead, it offers the continuity of care.

In this design, architecture speaks to the distant future in a language of form and story. It teaches that the buried waste remains dangerous. It teaches that generations have already worked to protect those who will come next. It invites the future to join in the act of protection, so that the message survives until the danger is gone.

Section SIX

Conclusion: Architecture as a Promise to the Future

The burial of nuclear waste confronts humanity with a profound responsibility. The act of sealing hazardous material beneath the earth does not conclude that responsibility. It begins it. The future will inherit the consequences of the present. Architecture must therefore become a vessel for memory and caution. It must speak clearly when language has changed. It must protect lives that have not yet been imagined.

The architectural proposal developed in this essay recognises that danger is not diminished by passing time. The monument grows because the duty to remember remains. Its expanding rings form a chronicle of human care. Each newly constructed layer records the continued willingness of society to defend those who come after. The design rejects the idea of a warning as a single inscription. Instead it embraces warning as a cultural tradition.

Communication across deep time requires a form of meaning that rises above the instability of belief and language. In this context architecture becomes a moral voice. It holds memory in stone and teaches caution through experience. The hostile interior environment warns instinctively. The narrative reliefs reveal why the danger exists. The continuous expansion shows that the peril is not history but persisting fact.

The task of safeguarding nuclear waste reaches into ages beyond comprehension. Although we cannot predict how future communities will think or speak, we can acknowledge what they must continue to know. They must recognise the site. They must understand that the buried material remains unsafe. They must see that previous generations cared enough to protect them.

This proposal uses architecture to express that valuation of life. It argues that a monument can be more than a boundary. It can be a promise. It can be an agreement across centuries that danger will never be forgotten. The future will not be left to find the hazard without guidance.

The true measure of success for any nuclear waste repository will not be the engineering knowledge that created it. It will be the lives preserved long after its builders are gone. An architecture that grows with time can serve that purpose. It becomes a silent partner to human history, speaking through scale and form when all else has fallen quiet.

The work of warning will continue until the earth beneath the monument no longer threatens the living. If that day comes many thousands of years from now, the expansion of the rings will finally stop. The last ring will stand as evidence that every generation fulfilled its duty. The architecture will no longer guard against harm. It will bear witness to perseverance.

Until that time arrives, this architecture commits the present to protect the future. It calls upon those who follow to uphold the same commitment. Through its enduring presence it declares the essential truth that safeguarding life is not temporary. It is a responsibility that reaches beyond any single moment in time and into the greatest depths of human possibility.

Section SEVEN

References

Human Interference Task Force (1984) Reducing the likelihood of future human activities that could affect geologic high level waste repositories. Battelle Memorial Institute, Office of Nuclear Waste Isolation.

Sandia National Laboratories (1993) Expert judgment on markers to deter inadvertent human intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant. Albuquerque: Sandia National Laboratories.

Trauth, K. M., Hora, S. C. & von Winterfeldt, D. (1991) Expert judgment on inadvertent human intrusion into the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant. Sandia National Laboratories report SAND90-3063.

Posiva (2012) On geological disposal of spent nuclear fuel. Posiva Oy, Finland.

Öhman, A. (2005) ‘The role of the amygdala in human fear: automatic detection of threat’, Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30(10), pp. 953–958.

Larson, C.L., Aronoff, J., Sarinopoulos, I.C. & Zhu, D.C. (2009) ‘Recognising threat: a simple geometric shape activates neural circuitry for threat detection’, Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 21(8), pp. 1523–1535.

Pakai-Stecina, D.T. et al. (2023) ‘Visual features drive attentional bias for threat’, [Journal of experimental psychology or similar]. [Include full journal details when known]

Smarthistory (2023) On Chauvet Cave and Altamira Cave art. Smarthistory. Available at: smarthistory.org [Accessed date].

Royal Society of Chemistry (2020) ‘Prehistoric pigments: why cave paintings last so long’, RSC Education. Available at: edu.rsc.org [Accessed date].

Britannica (2025) ‘Lascaux’, Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at: britannica.com [Accessed date].

British Museum (2022) Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and inscriptions. British Museum publications.

WIPP Expert Group (1993) Marker design for the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant. United States Department of Energy / Sandia National Laboratories.

Alyssa Denise Walsh

2025