Clune Park Estate

Project Overview

Clune Park Estate, Port Glasgow, is one of Scotland’s most frequently cited examples of urban decline, often discussed in terms of vacancy, risk, and demolition. This project proposes an alternative reading of the estate, approaching it not as a failed environment to be erased, but as a site of architectural, social, and cultural potential.

Developed as a long-form regeneration study, the project investigates how Clune Park might be reinhabited through architectural retention, self-help housing, and cultural infrastructure, rather than wholesale clearance. It brings together historical analysis, housing policy research, and spatial strategy to question demolition-led regeneration models and to explore more socially constructive approaches to renewal.

At its core, the proposal responds to two intersecting challenges. The first is the loss of historically significant urban fabric through large-scale clearance, particularly within post-industrial Scottish towns. The second is the persistent lack of accessible housing, opportunity, and support for young people, evidenced by high levels of youth unemployment, economic inactivity, and homelessness across Scotland. The disuse of viable housing stock such as Clune Park highlights a critical disconnect between housing need and regeneration policy.

The estate itself consists of 430 flats across 45 four-storey tenement buildings, resulting in one of the highest housing densities in Inverclyde. Once a thriving community tied to the success of shipbuilding along the River Clyde, the area experienced prolonged decline through the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Today, occupancy across the estate is estimated to be below ten percent, with many buildings wholly unoccupied and the area identified as having some of the highest levels of below-tolerable standard housing in the region.

Current regeneration proposals approved by Inverclyde Council prioritise demolition of the estate to enable new social housing development. While acknowledging the scale of deterioration, this project critiques the loss of architectural history and social memory implicit in such an approach. It argues that demolition forecloses alternative possibilities for reuse, participation, and community-led renewal.

In response, the proposal reimagines Clune Park as a mixed-use arts and housing district, combining affordable accommodation, studios, performance spaces, and communal infrastructure. Central to this vision is a self-help housing model, in which unemployed and under-housed young people are directly involved in the refurbishment process, gaining skills, agency, and a guaranteed place within the regenerated estate. Cultural production is positioned not as an embellishment, but as a structural component of regeneration, supporting public engagement, identity, and long-term resilience.

Rather than presenting a fixed masterplan, the project treats regeneration as a layered and evolving process. Clune Park is positioned as a test case for how neglected estates might be reactivated through retention, social investment, and cultural infrastructure, offering an alternative framework for regeneration across post-industrial contexts in Scotland.

Site Context and Historical Background

The Clune Park Estate is located in Port Glasgow, Inverclyde, on the south bank of the River Clyde. The estate occupies a prominent position within the town’s urban fabric, adjacent to Glasgow Road and within close proximity to the waterfront. Its scale, density, and architectural character make it a significant component of Port Glasgow’s nineteenth-century expansion, despite its current condition.

Developed in the late nineteenth century, Clune Park was constructed to accommodate workers employed in the Clyde’s shipbuilding and associated industries. The estate’s tenement blocks reflect the period’s emphasis on high-density urban living, with four-storey masonry buildings arranged along a clear street grid. At the time of construction, Clune Park formed part of a thriving and optimistic settlement shaped by industrial prosperity and strong local employment.

Over the course of the late twentieth century, structural economic decline within the Clyde shipbuilding industry had a profound impact on Port Glasgow and its housing stock. Key community buildings within Clune Park, including the local church and school, closed during the 1990s, severing important social and civic anchors. As employment opportunities diminished and population levels fell, the estate entered a prolonged period of neglect and disinvestment.

In the early twenty-first century, the condition of the estate deteriorated rapidly. Of the original 430 flats, distributed across 45 four-storey tenement buildings, occupancy has fallen to an estimated level of less than ten percent. Many buildings are now wholly unoccupied, and the estate records the highest levels of below-tolerable standard housing and void rates of any neighbourhood area within Inverclyde. There are no resident owners remaining within the estate, and the area has become increasingly stigmatised within public and media discourse.

Despite this decline, Clune Park retains a substantial amount of its original urban structure and architectural fabric. The repetitive tenement form, consistent street widths, and robust masonry construction continue to define the estate’s character, even in a state of disrepair. The scale of the housing stock and its proximity to existing transport routes and the River Clyde suggest a latent capacity for reuse that is often overlooked within demolition-led regeneration narratives.

Port Glasgow itself has experienced sustained population decline over recent decades, falling from over nineteen thousand residents in the early 1990s to approximately fifteen thousand by the 2011 census. This broader demographic contraction has compounded pressures on the town’s housing market and public infrastructure, contributing to cycles of vacancy and decline in areas such as Clune Park.

Recent events have further underscored both the fragility and significance of the estate’s built fabric. In August 2023, a fire destroyed much of the former Clune Park School, reducing the building to its outer walls. The loss of the school highlights the risks associated with prolonged vacancy, while simultaneously reinforcing the urgency of strategic intervention if remaining historic structures are to be retained.

Taken together, the site’s location, history, and current condition position Clune Park as a critical case study within contemporary Scottish regeneration discourse. The estate embodies the intersecting challenges of post-industrial decline, housing vacancy, and heritage at risk, while also presenting a rare opportunity to reconsider how large-scale tenement estates might be reactivated through retention-led and socially engaged regeneration strategies.

Social Context and Housing Crisis

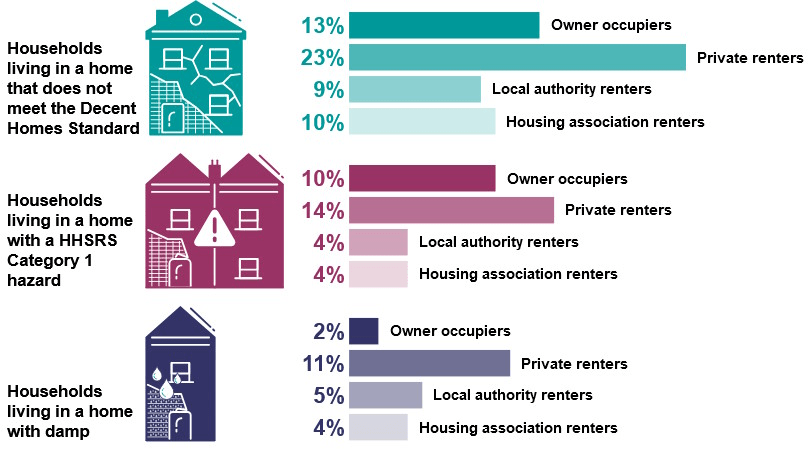

The regeneration of Clune Park Estate must be understood within the wider social and housing context facing young people in Scotland. Structural changes in employment, rising housing costs, and reductions in secure tenancies have placed increasing pressure on those aged sixteen to twenty five, particularly in post-industrial towns where economic opportunities are limited.

Between April 2022 and March 2023, the estimated unemployment rate for sixteen to twenty four year olds in Scotland stood at 9.6 percent, while the economic inactivity rate reached 37.1 percent. Although these figures are marginally lower than the United Kingdom average, they nonetheless represent a substantial proportion of young people excluded from stable employment and training pathways. Economic inactivity at this scale has long-term consequences, limiting access to housing, skills development, and social mobility.

Housing insecurity further compounds these challenges. In the same period, more than eight thousand homeless applications were submitted by young people aged sixteen to twenty five, marking a four percent increase in youth homelessness and an eleven percent rise in applications involving mental health needs. These figures indicate not only a shortage of affordable housing, but also a lack of supportive environments capable of addressing the complex social pressures faced by young people at the point of housing crisis.

Government policy acknowledges the severity of this issue. An independent report published by the Scottish Government under recommendation fourteen states that the government should be actively considering how it can maximise the availability of affordable housing options for young adults across all tenures. Despite this recognition, the supply of appropriate housing remains insufficient, particularly in areas where large quantities of existing housing stock have been left vacant or earmarked for demolition.

The continued disuse of estates such as Clune Park exposes a critical contradiction within current housing and regeneration strategies. At a time of acute housing need, significant quantities of potentially viable accommodation remain empty, deteriorating, and excluded from use. The absence of residents not only accelerates physical decay, but also removes opportunities for community formation, skills development, and local economic activity.

This project positions housing not simply as shelter, but as social infrastructure. It argues that regeneration strategies which fail to engage with employment, participation, and long-term support risk reproducing the very conditions that lead to decline. By targeting unemployed and under-housed young people through a self-help housing model, the proposal seeks to align housing provision with skills acquisition, collective responsibility, and community resilience.

Within this framework, Clune Park is understood not as an isolated problem, but as symptomatic of broader systemic failures in the relationship between housing policy, youth opportunity, and regeneration practice. Addressing the estate’s future therefore requires an approach that recognises social need as a primary driver of architectural intervention, rather than a secondary consideration.

Existing Regeneration Strategy and Critique

In response to the prolonged decline of Clune Park Estate, Inverclyde Council has pursued a regeneration strategy centred on large-scale demolition and redevelopment. An initial masterplan for the area was presented to the committee in 2018, proposing the clearance of the existing tenement buildings and their replacement with new social housing. While intended to address issues of vacancy and deterioration, the plan encountered challenges relating to affordability and delivery.

In August 2023, a further report was submitted to Inverclyde Council’s Environment and Regeneration Committee outlining progress toward a revised masterplan. The purpose of this update was to reassess the feasibility of redevelopment in light of changing market conditions, funding constraints, and an evolving understanding of housing need within Inverclyde. The revised proposals continued to prioritise demolition as the primary mechanism for regeneration, with updated layouts exploring alternative site footprints and potential development partnerships.

The publicly stated aim of the current strategy remains the demolition of all forty five tenement buildings within the estate. This approach reflects a broader tendency within regeneration policy to treat severely deteriorated housing as irreparable, positioning clearance as the most expedient route to renewal. While acknowledging the challenges posed by vacancy, antisocial behaviour, and physical decay, this project questions whether demolition represents the most socially and environmentally responsible response.

The wholesale removal of the existing estate would result in the loss of a substantial quantity of historic urban fabric. Clune Park’s tenements, despite their condition, retain architectural and typological significance as part of Port Glasgow’s nineteenth-century development. Demolition would erase not only physical structures, but also the spatial logic, density, and street relationships that define the estate’s character and connection to the wider town.

Beyond architectural considerations, demolition-led regeneration risks severing opportunities for participation and reuse. Clearance forecloses the possibility of incremental refurbishment, skills-based engagement, and community-led renewal, replacing these with development models that are often dependent on external funding, long construction timelines, and reduced local involvement. In areas experiencing population decline, such approaches may struggle to deliver the social vitality they seek to create.

This project positions the existing masterplan as a missed opportunity to explore alternative forms of regeneration that retain and adapt, rather than replace, the estate. By framing Clune Park primarily as a site for clearance, current proposals overlook the potential of the existing housing stock to address pressing social needs, particularly for young people facing unemployment and housing insecurity.

Rather than rejecting the need for intervention, this critique calls for a recalibration of regeneration priorities. It argues for an approach that recognises retention, adaptation, and participation as viable and valuable strategies, capable of aligning housing provision with social repair. In doing so, the project seeks to demonstrate how estates like Clune Park might function not as liabilities to be removed, but as foundations for inclusive and resilient regeneration.

Project Intent and Regeneration Framework

The project proposes an alternative regeneration framework for Clune Park Estate grounded in architectural retention, social participation, and cultural production. Rather than approaching the estate as a blank slate for redevelopment, the proposal treats the existing tenement fabric as a structural and social resource capable of supporting long-term renewal.

At the core of this framework is the belief that regeneration should extend beyond physical renewal to address social and economic exclusion. The project therefore aligns architectural intervention with opportunities for skills development, employment pathways, and community formation, particularly for young people who are disproportionately affected by housing insecurity and unemployment.

A central component of the proposal is the implementation of a self-help housing model targeted at unemployed and under-housed young people. Prospective residents are actively involved in the refurbishment and adaptation of existing buildings, gaining practical construction skills while contributing directly to the regeneration of the estate. In return, participants are offered secure and affordable housing within Clune Park upon completion, establishing a clear relationship between labour, learning, and long-term residency.

Cultural infrastructure is positioned as a parallel driver of regeneration. The proposal reimagines Clune Park as an arts-led district, incorporating studios, galleries, performance spaces, and educational facilities within the retained urban fabric. These spaces are intended to support creative production, public engagement, and collaboration with local schools, universities, and cultural organisations. Culture is not treated as an embellishment, but as a mechanism for reactivating public space, attracting sustained use, and reshaping the perception of the estate.

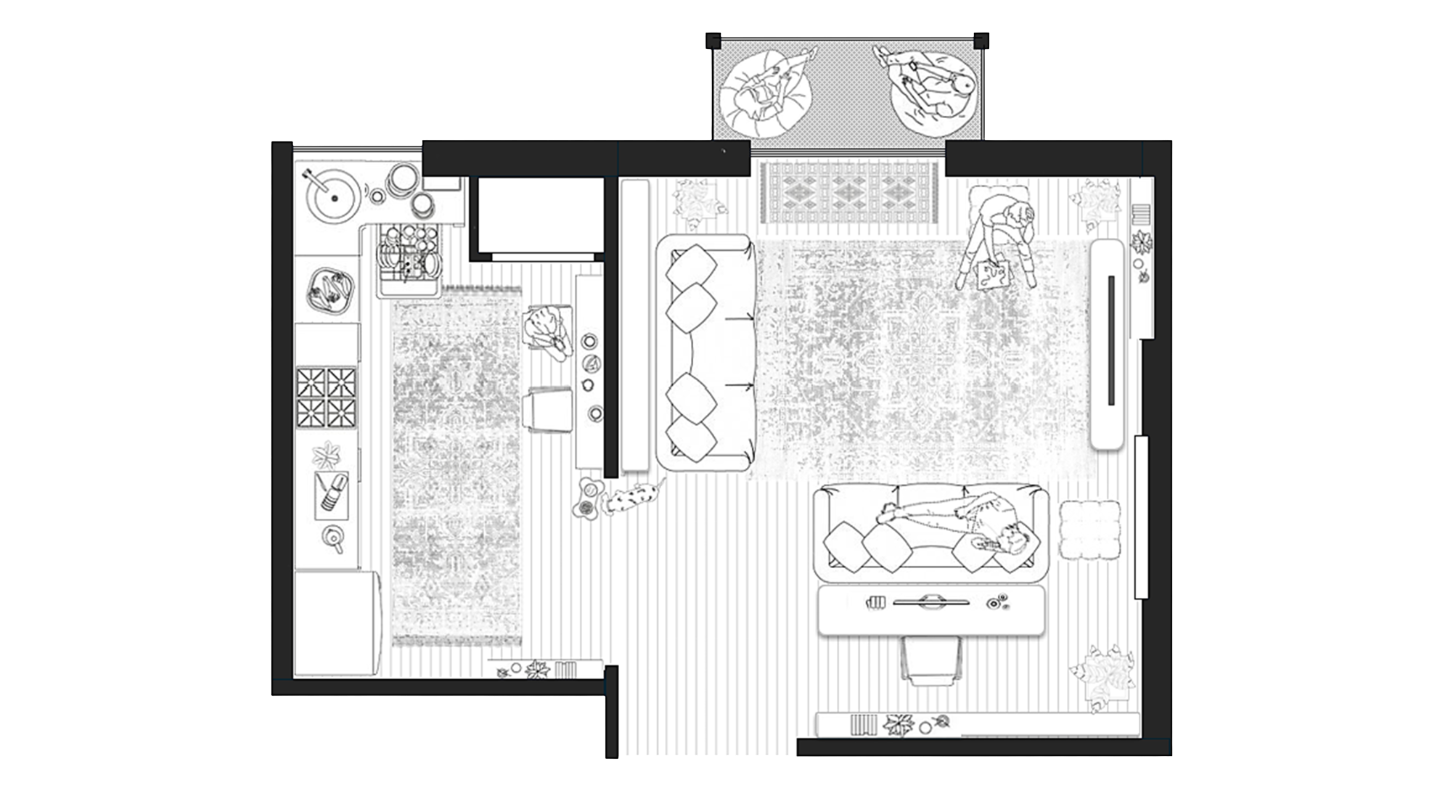

The regeneration framework also prioritises the quality of everyday living. Private domestic space is balanced with shared and communal environments, recognising the importance of dignity, autonomy, and social interaction within high-density housing. The existing scale and repetition of the tenement blocks are used to support both individual privacy and collective life, rather than being replaced with lower-density suburban typologies.

Environmental and economic sustainability are embedded within the framework through strategies that favour reuse over replacement. Retaining the existing buildings reduces material waste and embodied carbon, while incremental refurbishment allows regeneration to occur in phases, responding to available resources and evolving community needs. This approach supports adaptability and resilience, avoiding the risks associated with large, single-phase redevelopment projects.

Taken together, the project establishes Clune Park as a model for regeneration that is participatory, retention-led, and socially grounded. It proposes a framework in which architecture acts as an enabler of opportunity, positioning housing, culture, and community as interdependent components of a cohesive and durable regeneration strategy.

Self-Help Housing and Community Participation

Self-help housing forms a central pillar of the proposed regeneration strategy for Clune Park Estate. The project adopts this model as a means of directly addressing youth unemployment, housing insecurity, and social exclusion through active participation in the regeneration process. Rather than treating residents as passive recipients of housing, the proposal positions them as contributors to the physical and social reconstruction of the estate.

The self-help housing model is targeted primarily at unemployed and under-housed young people. Participants are invited to take part in the refurbishment of existing tenement buildings through structured, supervised programmes that combine practical construction work with skills training. This approach enables individuals to acquire transferable skills in building maintenance, repair, and adaptation, while simultaneously contributing to the improvement of their future living environment.

Participation in the refurbishment process is directly linked to long-term housing security. Upon completion of the works, participants are offered guaranteed accommodation within the regenerated estate, establishing a clear relationship between labour, learning, and residency. This structure fosters a sense of ownership, responsibility, and attachment to place, reducing the likelihood of transient occupancy and supporting the formation of a stable community.

Community participation extends beyond construction activity. Prospective residents, local artists, and members of the surrounding area are encouraged to engage in collective initiatives such as communal painting days, gardening projects, and public art production. These activities serve to build social cohesion, lower refurbishment costs, and create a shared identity for the estate. The process of making and maintaining the environment becomes a social act, reinforcing connections between residents and their surroundings.

The proposal also recognises the importance of appropriate support structures. Self-help housing is conceived not as informal labour, but as a regulated and guided process involving professional oversight, partnerships with training providers, and collaboration with local organisations. This ensures that participation remains safe, meaningful, and accessible, while maintaining standards of construction and habitation.

By embedding participation within the regeneration framework, the project challenges conventional top-down models of redevelopment. It argues that regeneration is most effective when residents are directly involved in shaping their environment, particularly in contexts where long-term vacancy has eroded social networks and trust. In the case of Clune Park, self-help housing is proposed as both a practical mechanism for refurbishment and a catalyst for rebuilding community life.

Cultural and Artistic Strategy

Cultural production is positioned as a fundamental component of the proposed regeneration of Clune Park Estate, operating alongside housing and participation as a driver of long-term renewal. The project reimagines the estate as an arts-led district, where creative activity contributes to economic opportunity, public engagement, and the reactivation of underused spaces.

The proposal incorporates a network of art studios and galleries distributed throughout the estate, providing affordable spaces for emerging artists to work and exhibit. These spaces are integrated within the existing tenement fabric, taking advantage of generous ceiling heights and repetitive floorplates to accommodate flexible creative use. By embedding studios within residential blocks, the project encourages daily interaction between living, working, and making.

The disused Clune Park Church is identified as a key civic anchor within the regeneration framework. Its conversion into a performance venue allows the building to support music, theatre, and dance, while preserving its architectural presence within the estate. Equipped with contemporary sound and lighting infrastructure, the space is intended to host both intimate performances and larger public events. The church may also function as a temporary exhibition venue, expanding its role as a cultural asset.

Education and skills development are integral to the cultural strategy. Workshops and training programmes are proposed across a range of artistic disciplines, including visual arts, performance, and digital media. These programmes are designed to support young people in developing creative skills alongside practical training acquired through the self-help housing model. Partnerships with local schools, universities, and cultural organisations are encouraged to provide resources, mentorship, and opportunities for collaboration.

Public culture plays a vital role in reshaping the identity of the estate. A street art competition is proposed for building façades along Glasgow Road, linking Clune Park to the wider Glasgow City Council Mural Trail initiative. This strategy increases the visibility of the estate, attracts visitors, and repositions the area within regional cultural networks. Murals and installations created by resident artists contribute to a shared sense of place and authorship.

Regular events and festivals form a further layer of cultural engagement. Performances, exhibitions, and community workshops are envisaged as recurring activities that bring residents and visitors together, fostering cultural exchange and sustained use of public space. These events support local economies while reinforcing the estate’s identity as a centre for creative production.

Through this integrated cultural strategy, the project seeks to move beyond temporary placemaking interventions. Culture is treated as infrastructure rather than spectacle, supporting livelihoods, education, and social connection. In doing so, the regeneration of Clune Park is framed not only as a housing project, but as a cultural ecosystem capable of generating lasting social and economic value.

Design Principles and Spatial Strategies

The spatial strategy for the regeneration of Clune Park Estate is guided by a set of architectural principles that prioritise retention, habitability, and social interaction within a high-density urban environment. Rather than imposing a new formal language, the proposal works with the existing tenement structure, adapting and enhancing it to support contemporary living and collective use.

A key principle is the balance between private and communal space. Within the tenement blocks, individual dwellings are designed to retain a clear sense of privacy and domestic autonomy, recognising the importance of personal space in high-density housing. This is complemented by a network of shared environments, including roof gardens, terraces, and pedestrian streets, which support social interaction without compromising individual dignity.

Painted façades form a visible and symbolic component of the spatial strategy. The proposal explores the use of colour as a means of identity-making and community participation, particularly along prominent routes such as Glasgow Road. Painting is conceived as a collective process, involving residents, local artists, and community members through organised events. This approach reduces refurbishment costs while allowing residents to directly contribute to the visual character of the estate.

Outdoor space is extended vertically through the introduction of communal roof gardens. Flat roofs along streets such as Robert Street are utilised as shared terraces, offering views toward the River Clyde and providing access to green space within a dense urban context. These roof gardens function as informal social spaces and support environmental goals by increasing urban biodiversity.

Environmental strategies are integrated into the spatial framework through the use of green roofs, rainwater harvesting systems, and solar panels where appropriate. These interventions contribute to improved thermal performance, water management, and reduced environmental impact, while reinforcing the project’s emphasis on reuse rather than replacement.

Pedestrianisation is employed as a key tool for improving the quality of the public realm. Side streets within the estate are prioritised for pedestrian use, reducing vehicle dominance and creating safer, more sociable environments. Limited vehicle access is retained where necessary for servicing and emergency use, ensuring functionality while maintaining a human-scaled streetscape.

In certain locations, variations in roof height and building condition inform the introduction of penthouse-level accommodation rather than communal gardens. This strategy allows additional housing to be accommodated without expanding the site footprint, while responding pragmatically to structural constraints. Revenue generated through these units may contribute to the long-term financial sustainability of the regeneration.

Taken together, these design principles establish a spatial framework that is adaptable, participatory, and sensitive to context. The proposal demonstrates how existing tenement estates can be transformed through incremental interventions that enhance liveability, environmental performance, and community life without erasing their architectural identity.

Precedent Logic and Comparative Studies

The regeneration strategy proposed for Clune Park Estate is informed by a range of international precedents that demonstrate alternative approaches to housing renewal, pedestrianisation, and community-led development. These examples are not treated as stylistic models, but as evidence of how social, spatial, and environmental principles can be successfully embedded within urban regeneration.

A recurring theme across the selected precedents is the prioritisation of pedestrian movement and shared public space. In districts such as Vauban in Freiburg and the Superblocks programme in Barcelona, car traffic is limited or redirected to the perimeter, allowing internal streets to function as social spaces rather than transport corridors. These projects demonstrate how pedestrian-first environments can reduce noise and pollution while fostering interaction, safety, and a sense of collective ownership. This logic directly informs the proposed pedestrianisation of Clune Park’s side streets, where reduced vehicle dominance supports community life within a dense residential setting.

Community participation in construction and management is another critical precedent strand. In Vauban, former military barracks were transformed through resident-led building cooperatives, enabling incoming communities to shape their environment directly. This model illustrates how collective involvement can generate both social cohesion and high-quality housing outcomes. Such precedents underpin the project’s adoption of a self-help housing framework, aligning physical regeneration with skills development and long-term residency.

The organisation of movement networks in places such as Houten in the Netherlands further demonstrates how dense residential environments can remain accessible without prioritising cars. By separating vehicular routes from pedestrian and cycling networks, Houten achieves safety and convenience while maintaining connectivity. This principle supports the proposal’s emphasis on walkability within Clune Park and its integration with wider transport routes in Port Glasgow.

Shared-street models, including the Dutch woonerven and neighbourhoods such as Nørrebro in Copenhagen, provide additional insight into how residential streets can function as multi-use social spaces. Through low-speed design, landscape integration, and visual cues that prioritise pedestrians, these environments encourage everyday social interaction while maintaining functional access. Such approaches inform the proposed reconfiguration of Clune Park’s residential streets as places for gathering rather than passage.

The inclusion of Central Milton Keynes highlights the long-term value of separating pedestrian and vehicular infrastructure at the urban scale. Although developed as a new town rather than a regeneration project, its redway system demonstrates how continuous, non-motorised routes can enhance safety and access to green space. This reinforces the importance of coherent pedestrian networks within regeneration strategies, particularly for young residents without access to private vehicles.

Collectively, these precedents demonstrate that successful regeneration does not rely on wholesale clearance or iconic redevelopment. Instead, they reveal the effectiveness of incremental change, community involvement, and spatial prioritisation that places everyday life at the centre of design decision-making. The Clune Park proposal draws from these lessons to argue for a regeneration approach that is socially engaged, environmentally responsible, and adaptable to local context.

Key Interventions and Site Response

The spatial response to Clune Park Estate is articulated through a series of targeted interventions that work with the existing urban structure rather than replacing it. These interventions are organised around key buildings, streets, and collective spaces, allowing regeneration to occur incrementally while maintaining the integrity of the estate’s historic layout.

Clune Park School and Centre of Education

Clune Park School, constructed in 1887, occupies a prominent position within the estate and historically functioned as a civic anchor. Designed by H. and D. Barclay, the building’s classical composition and masonry construction contribute significantly to the architectural character of the area. Following prolonged vacancy, the school was listed on the register of endangered buildings, and in August 2023 a fire destroyed much of the structure, leaving only the outer walls intact.

The proposal responds by retaining the surviving fabric and incorporating the former school into a new Centre of Education. This intervention aligns with the initial phase of the existing masterplan while extending its ambition. The adapted building is envisioned as a hub for learning, workshops, and skills development, supporting both the self-help housing programme and the wider cultural strategy. Retention of the school façade preserves a key element of the estate’s architectural memory while allowing new uses to be embedded within its footprint.

Clune Park Church as Performance Space

The former Clune Park Church of Scotland, built in 1905 and closed in 1997, is a Category B listed building and one of the few structures within the estate protected from demolition. Its architectural presence and internal volume make it well suited to reuse as a cultural venue.

The proposal converts the church into a performance space capable of hosting music, theatre, and dance. Contemporary sound and lighting infrastructure is integrated sensitively within the existing structure, allowing the building to accommodate both intimate performances and larger public events. The church may also function as a temporary exhibition space, supporting the estate’s role as a centre for cultural production. Its reuse establishes a strong civic focus and extends activity beyond residential use.

Residential Streets and Pedestrianisation

The residential streets of Clune Park are reconfigured to prioritise pedestrian movement and social interaction. Side streets including Bruce Street, Wallace Street, Clune Park Street, Maxwell Street, Wilson Street, and Montgomerie Street are proposed as pedestrian-dominant environments, with vehicular access limited to essential and emergency use.

This approach allows streets to function as shared social spaces rather than transport corridors. The removal of fences and unnecessary barriers improves permeability and visibility, while creating opportunities for informal gathering, play, and community activity. Secure parking provision is relocated to the edge of the site, reducing vehicle presence within the residential core while maintaining accessibility.

Robert Street and Roofscape Strategy

Robert Street occupies a distinctive position within the estate due to its orientation and views toward the River Clyde. The proposal introduces partial pedestrianisation along this route, balancing access requirements with improved public realm quality.

The flat roofs of the tenement buildings along Robert Street are utilised as communal roof gardens, providing shared outdoor space within a high-density context. These elevated terraces offer views across the river and contribute to biodiversity, while functioning as informal social spaces for residents. Where structural constraints or variations in roof height limit the feasibility of roof gardens, penthouse-level accommodation is introduced as an alternative, ensuring efficient use of the existing building envelope.

Façade Treatment and Identity

Façade interventions are used to establish identity and legibility across the estate. Buildings sharing a common access point are painted distinct colours, allowing residents and visitors to easily distinguish individual blocks. Painting is conceived as a participatory process, involving residents and local artists through organised events, reinforcing community ownership while reducing refurbishment costs.

Along Glasgow Road, predominantly windowless façades are identified as suitable surfaces for large-scale murals. These works form part of a proposed street art competition linked to the wider Glasgow City Council Mural Trail initiative, repositioning Clune Park within a regional cultural network and transforming a formerly neglected edge into a visible and celebrated frontage.

Environmental and Technological Strategies

Environmental performance and resource efficiency are addressed through a series of integrated strategies that prioritise reuse, incremental intervention, and low-impact technologies. Rather than relying on high-specification systems, the project focuses on practical measures that can be embedded within the existing tenement fabric and delivered alongside phased regeneration.

The retention of the existing buildings forms the foundation of the environmental strategy. By avoiding wholesale demolition, the proposal significantly reduces embodied carbon and material waste, recognising the environmental cost of clearance and new construction. Incremental refurbishment allows buildings to be upgraded over time, responding to available resources and evolving standards without requiring large, single-phase interventions.

Green roofs are introduced across selected tenement blocks to improve thermal performance, manage surface water, and increase urban biodiversity. These roofs support insulation, reduce heat loss, and create microhabitats within the dense urban fabric. In combination with communal roof gardens, they contribute to both environmental resilience and quality of life for residents.

Rainwater harvesting systems are integrated within the roofscape strategy, collecting and reusing water for irrigation and non-potable purposes. This reduces demand on mains water supply while supporting planted areas across the estate. The proximity of the site to the River Clyde reinforces the importance of responsible water management and landscape integration.

Solar panels are incorporated where roof orientation and structural capacity permit, contributing to on-site energy generation and reducing operational carbon. These installations are designed to be discreet and adaptable, allowing systems to be upgraded as technology develops. The emphasis remains on achievable, maintainable solutions rather than experimental systems requiring intensive management.

Passive design principles underpin all interventions. Improved insulation, controlled ventilation, and the optimisation of natural light are prioritised to enhance internal comfort and reduce energy demand. The tenement form, with its solid masonry construction and regular window rhythm, provides a robust framework for these improvements when combined with targeted upgrades.

Together, these environmental and technological strategies reinforce the project’s wider ethos of regeneration through retention and adaptation. By embedding sustainability within the existing fabric and aligning it with social and cultural objectives, the proposal demonstrates how environmental responsibility can be achieved without sacrificing architectural continuity or community engagement.

Conclusion and Ongoing Research

This project positions Clune Park Estate as a critical case study in contemporary regeneration practice, challenging demolition-led approaches through a framework grounded in retention, participation, and cultural production. By working with the existing tenement fabric, the proposal demonstrates how architectural continuity can support social repair, environmental responsibility, and long-term community resilience.

Rather than presenting regeneration as a fixed or singular outcome, the project treats it as an evolving process. The strategies proposed for Clune Park are intentionally incremental, allowing adaptation over time in response to changing social needs, economic conditions, and available resources. This approach contrasts with large-scale redevelopment models that often depend on extensive upfront investment and external delivery mechanisms, and which risk excluding local participation.

The integration of self-help housing within the regeneration framework is central to the project’s ambition. By aligning housing provision with skills development and guaranteed residency, the proposal reframes housing as social infrastructure rather than a commodity. Cultural and artistic production further reinforce this framework, positioning creativity as a means of sustaining engagement, reshaping identity, and attracting long-term investment in place.

Clune Park is not treated as an isolated problem, but as representative of broader challenges facing post-industrial towns across Scotland. The project therefore seeks to contribute to ongoing discourse around heritage-led regeneration, youth housing, and community participation. Its methods and principles are intended to be transferable, offering an alternative model for the reactivation of large tenement estates elsewhere.

This work remains an ongoing area of research and design development. Future exploration will focus on refining spatial proposals, testing governance and delivery models, and expanding the environmental strategies in greater technical detail. As a public-facing project, Clune Park also functions as a platform for continued reflection on how architecture can operate ethically within contexts of decline, vacancy, and social need.

Alyssa Denise Walsh

Independent regeneration and adaptive reuse research project