The Beijing Courtyard House

This essay was submitted as assessed coursework for the University of Cambridge architecture programme and is presented here to demonstrate academic research and writing.

The dwellings in China, Japan and Korea were dominated by the courtyard format up to the 19th century. With examples from one specific geographic region in one of those countries, discuss the evolution of the residential courtyard layout(s), and its/their relevance to your design ideas today in terms of spatial configuration, building construction, sustainable use of materials and cultural identity

Introduction

The dwellings in China were dominated by the courtyard format up to the 19th century with reference to the Beijing geographic region. The northern-style residential courtyard (Siheyuan) initially emerged as a response to the climate of the Beijing region, from the first developments of courtyard-style dwellings to the mass standardisation of the typology, Chinese courtyard dwellings evolved to embody the cultural values and traditional philosophical practices through the changing societal structures that occurred across over twenty Chinese dynasties, ultimately defining the story of Chinese architecture throughout its history. This essay explores the evolution of the style in terms of spatial configuration, building construction, sustainable use of materials and cultural identity and considers the utility of their modern applications.

Historical Context

Chinese Architecture can be traced back around 4,000 years, with early dwellings resembling the courtyard format from around 3,000 years ago. Archaeological discoveries suggest the courtyard format may have been developed as early (1211-255 BCE.) or even during the Shang dynasty (1766-1211 BCE.). While no physical records exist from earlier than 1766 BCE, it is possible courtyard type of housing was created sometime well before 255 BCE.

The Beijing Siheyuan

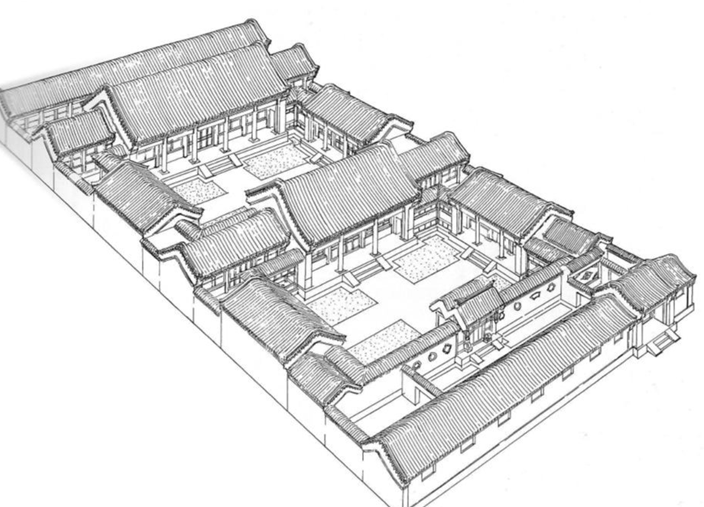

There are four categorisations of the northern style Beijing courtyard dwelling: Single, Double, Triple and Quadrangle. This format is maintained as the consistent design principle for residential dwellings. Whether historical or contemporary, each Beijing siheyuan is an oblong quadrangle encompassing at least one courtyard surrounded on four sides by individual halls.

The Beijing Siheyuan

Early Dynasties – The Single Courtyard Format

The unification of China in (221 BCE) marks the beginning of Imperial China. Courtyard dwellings would have typically been simple, single-courtyard residences that would have featured a central open courtyard space surrounded by rooms on all sides. These were characterised by symmetrical layouts signifying harmony, which is pursued and advocated by Confucianism. Building configurations were governed by the axial and symmetrical arrangements along the central axis that reflected values of social hierarchy. The Tang dynasty saw wealthier families adopt the courtyard approach through the integration of Confucian spatial principles.

Development of Double and Triple Courtyard Dwelling

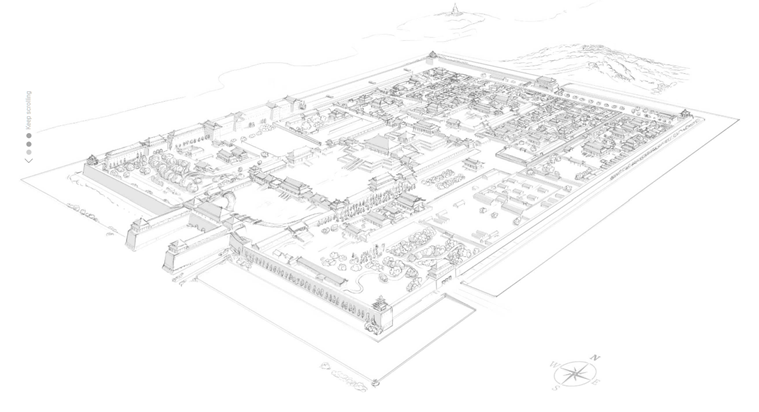

During the Ming dynasty, regulations on courtyard construction were enforced, as the middle classes were limited to three-bay courtyard construction. Courtyard houses became signifiers of the status of the family. The major north-south axis was critical in the symbolisation of social hierarchy and status. Traditionally, the depth (length) of the axis was a symbol of social position and wealth. The higher the social class, the longer the axis and the greater the number of yards. The courtyard format was exemplified in this period by the construction of the Palace City, later known as the Forbidden City, as part of the Yongle Emperor’s vision to establish Beijing as the imperial capital.

The Quadrangle Courtyard Dwelling

The quadrangle was the most developed courtyard format and became the typology for Beijing’s elite residences. Entrance to a Beijing Siheyuan is almost always through one Damen (Front Gate) onto the main street. This is typically set to the southeast side except for in the case of high nobility or wealthy families, where this is sometimes in the centre. The appearance of Damens was dependent on the wealth and social standing of the family. The Chinese believed that evil travelled in straight lines; therefore, staggering the entrance would prevent evil spirits from entering the household. Sitting in opposition to the main hall (Zhengfang), the front of the complex is usually the most public and active portion of the dwelling, including kitchens and space for servants and storage. There is a screen or spirit wall to shield the interior.

Spatial Influence of Familial Hierarchy

In the traditional Chinese family, a microcosmic society, there was an extremely strict pyramidical structure. Centred around the main courtyard (Nelyuan), the elders occupied the master’s residence (Zhengfang), while the side houses to the east (Dongxiangfang) and west (Xixiangfang) were occupied by younger family members. The inaccessibility of the central authority was designed not only as a symbol of his importance but also as a symbol of the distance between him and other members of the family. The master rooms were considered to have the best feng shui quality, while the two wing rooms symbolised the worship of the master. The prominence of the master rooms was reinforced by the fact that the major yard, in the house, took the shape of a rectangle with its longer axis running north and south This axis controlled the strictly symmetrical composition of the major yard. Everything in the courtyard seemed to focus on the master rooms, symbolising that the entire family was unified under a central power. To the rear of the complex was the northern hall (Houzhaofang), which was often used for storage or to house servants.

Building Construction and Material Sustainability

The Siheyuan approach to design used natural methods to insulate and ventilate in response to the changing Beijing climate. It is characterised by dense exterior walls forming an enclosure on four sides, typically constructed using brick or stone. Initially developed as a practical solution to combat the harsh northern climate, they provided shelter from the elements and monsoon weather conditions while offering thermal mass to insulate the structure. The courtyard, enclosed by the walls or buildings around it, takes on an introverted quality. Siheyuan proclaims seclusion and separation from the outside contrasted by a feeling of security and openness on the inside. Nelson Wu characterises this as an “implicit paradox of a rigid boundary versus an open sky”, where “the privacy is a partial one; horizontally the yard is separated from the street by the wall or the surrounding buildings, but it shares both the sky and the elements of the weather with other houses and yards”.

The interior walls were constructed using rice paper screens that could be ventilated in the summer. This approach to design harmonises with the natural environment to maintain comfortable year-round internal temperatures. The use of materials was an additional method of symbolising status. Common people could only use grey tiles in their courtyards, while the emperor utilised special materials such as glazed tile.

Building Construction and Material Sustainability

The architecture of today’s cities is often regarded as inhibiting healthy relationships between public and private spaces. While city populations are increasing and growing, the frequency with which people feel happy in such living arrangements is rapidly decreasing. Traditional Chinese courtyard houses exemplify how the distinction between the residence and the city can be curated through design. The walled arrangement creates a distinct and uninterrupted area inaccessible to the surrounding city. The courtyard approach centres the garden within the residential format, maintaining a peaceful atmosphere provided by interior views. This is a stark contrast to recent urban architectural development, which neglects the importance of private green space within the household.

The Importance of Preservation of Feng Shui Principles in Maintaining Cultural Identity

Feng Shui has long been a critical force in the development of Chinese architecture. The consistency of the characteristic of the courtyard style has been maintained throughout history as a direct result of this; the extensive history in which that courtyard style of architecture has remained centred as the primary residential form stands as evidence of the success of the design in its inhabitant of human life.

The recent change in the predominant approach to architecture fails to appreciate the refinement process that has occurred. Although the courtyard form has remained consistent in its dominance as the prominent form throughout Chinese history. It is not the only approach to residential architecture that has been taken within the region yet unlike the courtyard formant, popularity of alternative approaches have wavered in popularity and none have maintained dominance.

Practical Integration

While the desirability of the courtyard format is profoundly apparent, large-scale application of the style may be reduced to a utopian ideal in the modern urban landscape. Since the eras of China’s courtyard-dominated cities. Urban populations and land values have exponentially increased, leaving the traditional courtyard structure reserved for the wealthy. Integration of Siheyuan principles into modern urban design should replicate the courtyard format on a higher density scale, imploring elements such as shared gardens to create small communities in modern approaches to urbanisation such as co-housing.

Multi-Generational Living

The Chinese residential courtyard structure is exemplary of how multi-generational living can be successfully implemented into the structure of the architectural design to maintain a distinct separation of public and private space within the family unit. The courtyard structures’ infernal and enforced, generational hierarchy rooted in Confucian ideals are fundamentally significant components of the success of this approach to living.

Preservation of Chinese Cultural Identity

The Siheyuan is an embodiment of the Chinese cultural identity. It has developed alongside the Chinese population for millennia forming a symbiotic relationship of values and practices imbued within the architecture. The characteristics reflected in the Beijing courtyard dwelling may still be found in many Chinese people today: a cold outside with a warm inside; a modest surface with a proud interior; a manner that is reserved with strangers, but unrestrained, in style and content, with friends and family; and a speech that takes a meandering path. This architectural approach centres on values of respect for the hierarchical structure. While historically this may have been utilised as a tool to manifest this order in favour of those of the highest standing in the social hierarchy. The application of the underlying principles on a smaller scale within the family structure provides a sense of unity and identity to Chinese families. Implementation of these principles from the scale of the familial unit to the wider urban context can mitigate climate challenges caused by thoughtless design while continuing the legacy of Chinese architecture for future generations.

References

Hou, R. (1985). Collection of Beijing Historical Maps. Beijing: Beijing Publishing House.

Knapp, R. G. (1999). China’s old dwellings. University of Hawai’i Press.

Liu, D. (1979). Suzhou Classical Gardens. Beijing: China Construction Press.

Liu, Y. & Awotona, A. (n.d.). The traditional courtyard house in China: Its formation and transition.

Ma, B. (1999). The architecture of the quadrangle in Beijing. Tianjin: Tianjin University Press.

Sicheng, L. (1984). Chinese Architecture: A Pictorial History. New York: Dover.

Wu, N. (1963). Chinese and Indian Architecture: The City of Man, the Mountain of Gold, and the Realm of the Immortals. New York: George Braziller.

Xiong, C.-S. C. (2007). The features and forces that define, maintain, and endanger Beijing courtyard housing. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research , Spring, 2007, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 42-64.

Xu, P. (1998). “Feng-shui” models structured traditional Beijing courtyard houses. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, Winter, 1998, Vol. 15, No. 4, 271-282.

Zhang, D. (2020). Courtyard houses around the world: A cross-cultural analysis and contemporary relevance. Chinese Culture Publishing.

Alyssa Denise Walsh

University of Cambridge

2025